Would The Beatles Make It In Today's Music World?

MSNBC.com

Mon, 12 Jul 2010

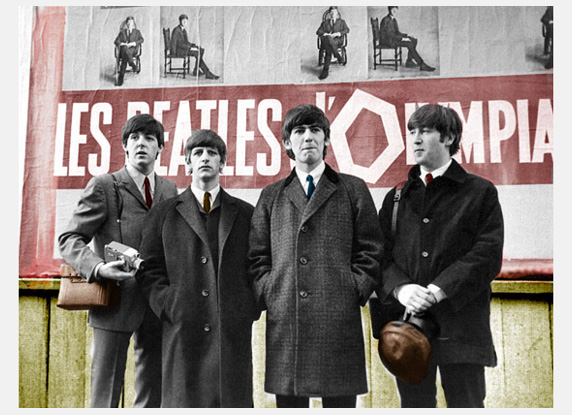

![]() et's start with a widely held belief: The music made in the '60s and '70s was vastly superior to the music being produced today.

et's start with a widely held belief: The music made in the '60s and '70s was vastly superior to the music being produced today.

"No, it's there if you want it," noted Peter Baron of the current crop. "Every year there are a lot of great records, but you have to go find them yourself. It's not like you'll hear them on the radio, because there is no radio.

"Every year there are probably 10 great albums that unfortunately people miss."

Baron isn't a music newbie trumpeting the cause of the modern downtrodden artists suffering in obscurity in the age of iTunes. He's a former music executive who spent 20 years on the label side with such companies as Interscope, Arista and Geffen before become a pioneering executive at MTV. He has a unique perspective on the music business, since he was at the forefront of the video revolution at MTV that bridged the eras of the 33 1/3 rpm album and the download.

The music business clearly has transformed dramatically from the days of the Beatles until now, when superacts are extremely rare. In fact, veterans like to say that there is no more music business, at least in the sense that there was a business model to guide artists, managers, executives, disc jockeys, advertisers and fans.

When the Beatles became famous in the UK in 1963, and then invaded the U.S. in February of '64, there was a finite number of record companies and a finite number of radio stations that played records made by those companies. There was a framework in place for success.

Andrew Loog Oldham was intimately familiar with it. As the manager of the Rolling Stones in the '60s, he helped guide the creative energies of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts & Co. while also devising a plan to sell the bad boys of rock and roll to the world.

"In the '60s, we had the advantage that the game was incremental," Oldham said. "For example, you were allowed to make a 45 rpm (single). If that did OK, then you were allowed another one, then a 33 1/3 EP. It was a very good process for an act to be able to pace themselves and grow."

Touring then, and now Then there was the other component for success, Oldham explained: touring.

"The only aspect that has remained the same between the '60s and now is the road -- it is king," he said. "It makes, breaks and finishes an act."

Today, even the road doesn't look the same. Members of Led Zeppelin aren't riding through the halls of a Los Angeles hotel on motorcycles. Van Halen isn't insisting on a bowl of M&Ms in its dressing room with all of the brown ones removed.

Today, the vast majority of artists don't have tour support from major record companies and have to go out-of-pocket in order to ply their trades beyond their home bases. They look to MySpace and other social networking outlets to get the word out about appearances, and about the actual music they make.

"You're putting up tour support for yourself until you break," said Los Angeles-based singer-songwriter Miranda Lee Richards, who recently appeared at Lilith Fair in Portland, Ore.

Richards (myspace.com/mirandaleerichards) also has experienced two distinct perspectives regarding the music business. She has released two CDs, but they came eight years apart. With her first, she had a deal with Virgin Records, which she got in 2001. Her most recent release, last year's Light of X, is on the indie label Nettwerk.

She said major labels tend to oversee more, and are more involved in the creative process. They might prod an artist into bringing in heavy-hitter musicians or collaborators. They also will likely steer you toward a more mainstream and commercial path.

With indies, there is more artistic freedom and less interference, but also less financial support.

"I think it (the current environment in the music business) benefits music tremendously, because I feel the music is artier," she explained. "There is still pop music, but indie music right now is more free, less constricted, the imagery is good and there are interesting presentations because it looks like bands are having fun and nobody's telling them (what to do). The best marketing plan always will be and still is great music. Especially now, more than ever, you have to do something extraordinary to get people's attention.

"But having zero resources is not beneficial. It makes things a lot harder. It's also weeded out people who were not doing it for the right reasons. Anybody who doesn't love music doesn't survive. Also, I've seen a lot of great bands break up because they just couldn't afford to do it anymore.

"Fortunately or unfortunately, it leaves it up to artists to handle their own business."

Sharing the wisdom of his experience

That's where John Hartmann comes in. A former record company executive and manager who worked with acts in the '70s such as the Eagles, Joni Mitchell, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, America, Poco and many others, he is now teaching a music business class at Loyola Marymount University in the Los Angeles area. He also offers his lectures online at holodigmmusic.com.

Hartmann addresses the question: How do you build an act today when the music is free?

(It should be noted that when he asks for a show of hands among his young students about how many of them download music without paying for it, most of the hands go up, he said.)

"If you can't make it at home, you can't make it anywhere," he explained. "If you can make it at home, you can make it anywhere. You don't need a record company, you don't need a tour."

Among other bits of advice, Hartmann urges artists to dominate their local market, to establish themselves within a 100-mile radius of where they live, and to not tour beyond that, because then expenses begin to pile up. "If you can't make it within 100 miles, then there's something wrong with your act," he said.

He also tells artists and bands to own their own publishing and masters, to sell CDs and merchandise at gigs, and to work with a professional record producer whenever possible rather than putting out homemade demos.

No love loss for major labels

If there is one common sentiment among music business people young and old, it's good riddance to the major labels, or at least what they became at the time Napster and other online sites began their downfall with file swapping.

"I am happy they are dead because they were horrible," Hartmann said. (A small handful do still exist, but they have branched more into the management end and so-called "360" deals with artists to compensate for the lack of record sales.)

"They were awful people," Hartmann said, "and it was their greed that prevented them from seeing the future."

Yet it wasn't all bad, especially in the '70s, said Mel Posner, a former president of Elektra Records who also worked as an executive at Geffen and DreamWorks. He spent 50 years in the business and remembers going to see Arthur Lee & Love at the Whiskey A Go Go on the Sunset Strip with a little warm-up act called The Doors.

"In those days, there was a lot more latitude by the record companies, because they were independent," Posner said. "They didn't have Wall Street looking over their shoulders. You invested in an artist not just for one album, but for a career. At Elektra, there was an ease, a more relaxed attitude about putting out albums and starting careers with artists."

But Posner said when multinational corporations bought up the record companies, it all started to go downhill. Now? "There's less passion in both the consumer and the record industries themselves," he said. "It's too easy for a record company now to say, 'Well, we tried,' and let's pass after only one album."

Yet through all this, the question looms: If the Beatles came along in today's music environment, would they become as big?

"Theoretically, they would," Hartmann said. "The bottom line in this business is talent. Talent rules. It's up to the artists' talent to determine whether they will prevail in the end." ![]()

|

|

|