The Digital Fab Four: Rating the Beatles CD's

By Steve Pond

Rolling Stone

July 16, 1987

![]() t was twenty years ago today/Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play." That line has been invoked an awful lot this year, as Capitol Records has turned the Greatest Album Ever into (Capitol says) "the most important and revealing compact disc release there can ever be." But as the newly digitized Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band blares from CD players everywhere, it's worth recalling lines from a less hallowed source, Blue Oyster Cult: "Things ain't what they used to be/And this ain't the Summer of Love."

t was twenty years ago today/Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play." That line has been invoked an awful lot this year, as Capitol Records has turned the Greatest Album Ever into (Capitol says) "the most important and revealing compact disc release there can ever be." But as the newly digitized Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band blares from CD players everywhere, it's worth recalling lines from a less hallowed source, Blue Oyster Cult: "Things ain't what they used to be/And this ain't the Summer of Love."

No, these are more sober and businesslike times, and the 1987 version of Pepper Fever is dramatically different from its 1967 precursor. Back then, the fever was a near-spontaneous, overwhelming reaction to a groundbreaking album that unerringly captured and sealed the moment for a worldwide youth community. Today, the fuss over Sgt. Pepper is, above all, the culmination of a carefully orchestrated, canny and lucrative marketing campaign.

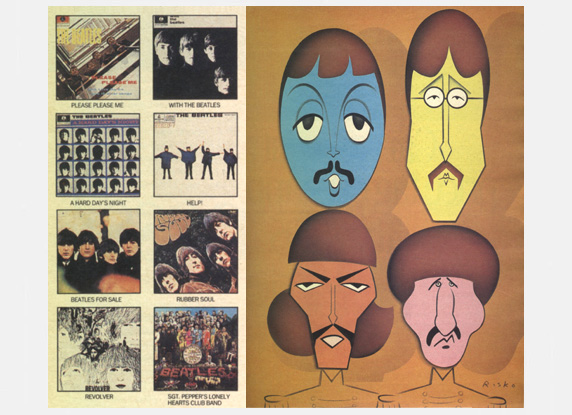

Capitol Records has smartly turned its 1987 series of Beatles reissues into an event. While ABKCO and Columbia dumped all the early Rolling Stones CDs onto the market at once, giving all but the die-hards far too much to choose from, Capitol has released the Beatles CDs in batches small enough to lure many fans into buying everything. The label also guaranteed a publicity blitz by making sure Sgt. Pepper would hit the stores on June 1st, the twentieth anniversary of its original release.

It hasn't always been smooth sailing with Capitol's marketing scheme. Aficionados protested the release of the first four records in mono, though Beatles producer George Martin said that the first two were only available in fake stereo versions that would have been far worse. And more casual American fans may have been confused by the albums themselves, since the CDs correspond to their British rather than far different American configurations. For nostalgia's sake, it might have been nice to have, say, The Beatles' Second Album or Yesterday and Today on CD -- but those albums didn't exist in Great Britain, and it's pointless to complain too loudly when the British LPs are longer and more intelligently compiled. (Still, the Beatles left many of their hit singles and standout tracks off the British albums, so you won't find "I Want to Hold Your Hand," "She Loves You," "We Can Work It Out," "Day Tripper" or several others on CD. Capitol says it is going to release CD compilations with all the missing songs, but then, some time ago, Capitol said it was going to standardize the Beatles' albums on both sides of the Atlantic, and that never happened.)

Album confusion aside, the CDs have other problems. Up until Sgt. Pepper, their running time averages less than thirty-four minutes apiece, which means that two complete albums could easily fit on a single disc, á la Motown's twofers series. Combining Beatles albums would have cut Capitol's profits and, it could be argued, disrupted the integrity of the individual records. Still, Rubber Soul and Revolver on one disc would have been the CD bargain of a lifetime.

Meanwhile, the naturally brighter CD sound is also shriller and sometimes more grating, mostly on the rock songs from Please Please Me and With the Beatles but to some degree on everything until Rubber Soul. The new technology adds some clarity, but it does far less for the Beatles than CDs have done for, say, Buddy Holly.

Capitol clearly wanted Sgt. Pepper ready for June 1st; it's possible the label was prepared to shortchange A Hard Day's Night and Beatles for Sale to get there. Though the early CDs have variable sound and occasionally shoddy packaging that crams the original LPs' photos and liner notes into inelegant graphic hodgepodges, Sgt. Pepper gets the treatment that becomes a legend most: significantly improved sound, extensive liner notes, a twenty-eight page booklet. After all, wasn't Sgt. Pepper the Beatles' big event?

Well, yes and no. Two decades ago, it seemed unquestionably the biggest and greatest album anybody had ever made; today, it doesn't even sound like the Beatles' best record. Of course, it's hard to stand back and dispassionately assess the Beatles' music: the pop revolution the group started may be two decades past, but it still claims virtually everyone over twenty-five, making it nearly impossible to hear "I Saw Her Standing There" or "Eight Days a Week" -- or, hell, to even look at the cover of With the Beatles -- with anything approaching objectivity.

In a way, it's startling that the music retains any freshness at all, twenty-odd years and countless elevator renditions later. But the key world may be effortless: the band worked as hard as anybody in rock & roll, but the playing sounds natural, easy, enormously potent but completely unforced. And while the early records are saddled with a few too many questionable cover versions (the Rolling Stones always had better taste in outside material), there's an unstoppable momentum. Try Please Please Me for the Beatles' unfettered joy at making music; With the Beatles for their growing toughness; A Hard Day's Night for the dazzling assurance of Lennon and McCartney's songs; Help! for the relatively quiet and understated way in which they consolidated their strengths.

After that, the Beatles got "mature": less adrenaline, more subtlety. And Capitol got serious. Though the digital transfer doesn't make this astonishingly rich batch of songs any better, the remixed Rubber Soul CD shows more signs of tinkering than the earlier releases: balances are changed, background parts made louder, John's intake of breath in "Girl" becomes far more prominent. Just as the recording technology got more sophisticated with Rubber Soul and Revolver, those albums' CDs sound fuller and cleaner (though Revolver wasn't digitally remixed, unlike Help! and Rubber Soul).

Then, Sgt. Pepper. As a collection of pop songs, it's not match for its two predecessors: "Girl" and "For No One" are timeless; "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" and "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" are inescapably tied to their times. But as a cultural artifact, as a landmark of its era, as an instant passage to the first Summer of Love, nothing else comes close. Few things are sadder than a once-revolutionary work whose bite has been eroded by time, but Sgt. Pepper survives because it's also a fun, playful, ambitious record, a mannered but terrific collection of songs with highlights as devastating as "A Day in the Life."

It's also the kind of record that seems to have been designed for compact disc, full of sonic showcases like "Lovely Rita" and "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite." This album, clearly, was transferred to CD as carefully as some of the others should have been: though tape hiss shows up in a few places, on the whole Sgt. Pepper gains a clarity and vividness the vinyl version simply doesn't have.

But if it whips up the same sort of hysteria the album prompted two decades ago, it'll mean that today's classic-rock, "music for the Big Chill generation" mentality is more dangerous and out of control than we ever imagined. The Beatles CDs are fun, expensive, occasionally revelatory -- and, for Capitol Records, highly profitable -- ways for us to hear some of the best rock ever recorded without the clicks, pops and scratches that most of our Beatles albums have accumulated through the years. But to turn them into more than that is a mistake. That was twenty years ago, after all, and this ain't the Summer of Love. ![]()

|

|

|